Our next stop is Semey. The town on the Irtysh River used to be called Semipalatinsk, because at its foundation in 1718 it consisted of a fortress surrounded by seven (Russian: sem) tents (Russian: palatki). After a drive of several hours through the once again breathtakingly beautiful, but this time quite varied steppe landscape, we arrived at our hotel “Semey” in the evening.

Immediately, Ina’s cousin, her husband and a couple of friends took us on a guided tour through Semey at night. The tour ended in a cheerful shashlik binge. Sveta is Kazakh-German, but stayed in the city during the great migration wave in the 90s. She probably missed the moment at some point, she says. She has no regrets. She knows Germany from visits to her relatives. Of course it is nice and orderly there, but also very rule-oriented, she thinks, and here there is a bit more freedom.

We learned that Semey’s development has stagnated somewhat since the administrative seat of the oblast was transferred from here to Oskemen. Probably the most important personality of this town is the Kazakh poet and thinker Abai Qunanbajuly (1845-1904). He is a national figure of the country, his works have been translated into numerous languages and he serves as the namesake for streets, squares and cultural institutions in Kazakh cities. Of course, there is also a square in Semey, the centre of which is adorned with an imposing statue of Abai. The memorial to the nuclear weapons tests is also impressive. On a site not far from Semey, called Polygon, the Soviet Union carried out nuclear weapons tests from 1949 to 1989. Under pressure from the Nevada-Semipalatinsk civic movement, led by the well-known poet Olshas Omarovich, the nuclear weapons test site was closed in 1991. Even today, residents of the nearby villages suffer from the health consequences, such as frequent cases of cancer.

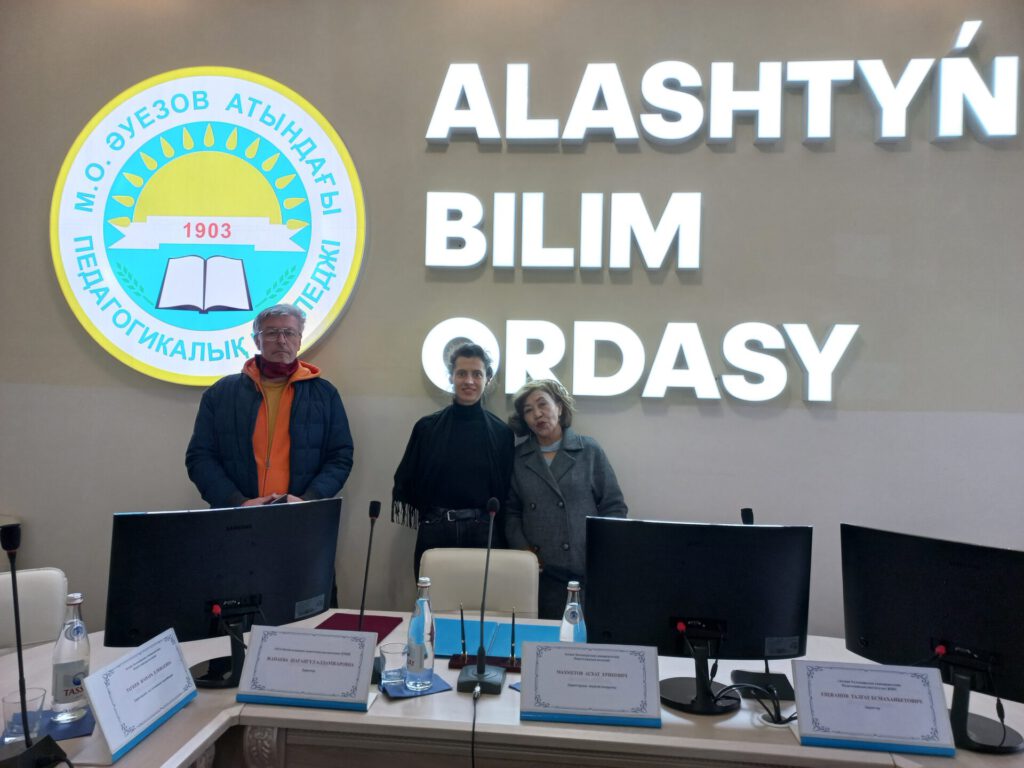

The following day we met Raissa, a former school friend of Ina’s mother. She took us to the dormitory and college of education where both of them once attended school. Raya herself hadn’t been there for over 40 years and was amazed that somehow nothing and yet everything had changed. Once again, we enjoyed Kazakh hospitality and spontaneity: the deputy director gave us a guided tour of the school building and told us about the present and past of this educational institution, which is highly respected throughout the country. A detour to the Kazakhstan-German “Rebirth” Association in the House of Friendship was just as indispensable as a visit to the local museum.

Raissa’s husband Orazbek, who had acquired the name “Otto” in Soviet times (similar to Volker’s Kazakh name), told of his former good knowledge of German, of which, unfortunately, hardly anything is left. In his home village, half of the inhabitants had been German and he was still in contact with some of them, even though they had long since emigrated to Germany. He and Raissa repeatedly emphasised the friendly cooperation between Kazakhs, Germans, Russians and other nationalities. Even today, about 33 different ethnic groups live in Semey.

We were able to experience in many different ways that hospitality is very important here. Whether it’s distant relatives or family friends you meet for the first time, employees in public institutions or vendors at the market – the openness and warmth of the people is more captivating than the splendour of Nur-Sultan or even the vastness of the steppe.